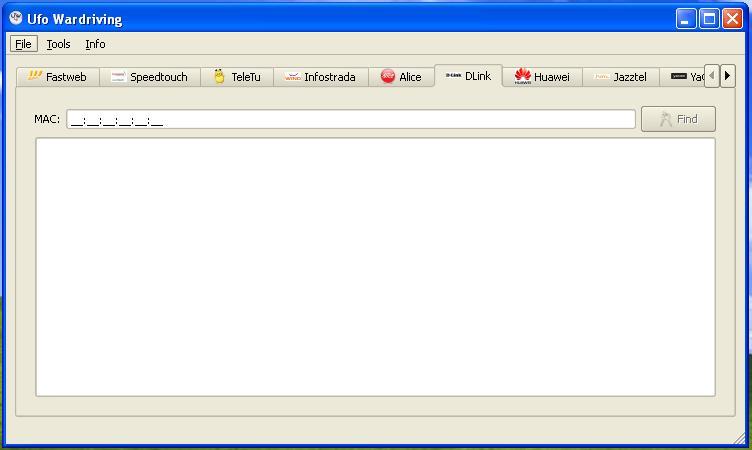

War Driving Software With Gps Mac

Wardriving is the act of searching for Wi-Fi wireless networks, usually from a moving vehicle, using a laptop or smartphone. Software for wardriving is freely available on the internet. Warbiking, warcycling, warwalking and similar use the same approach but with other modes of transportation.

- WiFiFoFum is a WiFi scanner and war driving software for Pocket PC 2003, Windows Mobile 5, and Smartphone editions. This version makes use of the latest features of.NET CF to give you the highest performance for war driving. With this version you can be confident your GPS logged coordinates for the networks you find are highly accurate, and can rely on a smooth user interface experience.

- GPS is used to track the location of the discovered networks immediately. Automatic associating is possible with randomly generated MAC addresses. Wellenreiter runs also on low-resolution devices that can run GTK/Perl and Linux/BSD (such as iPaqs).

- WiFiFoFum is a WiFi scanner and war driving software for Pocket PC 2003, Windows Mobile 5, and Smartphone editions. This version makes use of the latest features of.NET CF to give you the highest performance for war driving.

WiGLE (or Wireless Geographic Logging Engine) is a website for collecting information about the different wireless hotspots around the world. Users can register on the website and upload hotspot data like GPS coordinates, SSID, MAC address and the encryption type used on the hotspots discovered. In addition, cell tower data is uploaded and displayed.[1]

By obtaining information about the encryption of the different hotspots, WiGLE tries to create an awareness of the need for security by running a wireless network.[2]

Mac os x mail app type too small. Zoom in and out using a MacBook trackpadYou can also zoom in and zoom out your screen on a MacBook Pro trackpad. Again, hold down the ctrl key, but this time take two fingers and swipe upwards on the trackpad area to zoom in, then use your two fingers to swipe downwards to zoom out.This is very cool.

The first recorded hotspot on WiGLE was uploaded in September 2001. By June 2017, WiGLE counted over 349 million recorded WiFi networks in its database, whereof 345 million was recorded with GPS coordinates and over 4.8 billion unique recorded observations. In addition, the database now contains 7.80 million unique cell towers including 7.75 million with GPS coordinates.[3] By May 2019, WiGLE had a total of 551 million networks recorded.[4]

Mentions in Books[edit]

From Hacking for Dummies [5] to Introduction to Neography,[6] WiGLE is a well known resource and tool. As early as 2004, its database of 228,000 wireless networks was being used to advocate better security of Wifi.[7] Several books mentioned the WiGLE database in 2005,[8][9] including internationally,[10] and the association with vehicles was also becoming widely known.[11] Some associations of WiGLE have been positive, and some have been darker.[12][13][14] By 2004, the site was sufficiently well known that the announcement of a new book quoted the co-founder, saying “This is the ‘Kama Sutra’ of wardriving literature. If you can't wardrive after reading this, nature has selected you not to. This is the first complete guide on the subject we’ve ever seen (it mentions us). Don't quote me on that.”–Bob “bobzilla” Hagemann, WiGLE.net CoFounder' and a shortened quote appeared on the book's cover.[15][16]

Mentions in Academic Papers[edit]

In early days, circa 2003 the lack of mapping was criticized, and was said to force WiFi seekers to use more primitive methods. 'The most primitive method disseminated is warchalking, where mappers inscribe a symbolic markup on the physical premises to indicate the presence of a wireless network in the area.' Regarding WiGLE in particular, it was said, 'The Netstumbler map site and the Wireless Geographic Logging Engine store more detailed wardrive trace data, yet do not offer any visualization format that is particularly useful or informative.' [17] By 2004 others felt differently, however, and a WiFi news site said about 'the fine folks at wigle.net who have 900,000 access points in their wardriving database,' 'While the maps aren't as pretty, they're quite good, and the URLs correspond to specific locations where WiFiMaps hides the URL-to-location mapping.' [18] In late 2004, other authors stated, 'that war driving is now ubiquitous: a good illustration of this is provided by the WiGLE.net online database of WAPS.' They also said, 'The motherload of WAP maps is available on the Wireless Geographic Logging Engine Web site (wigle.net). Circa late September 2004, WiGLE’s database and mapping technology included over 1.6 million WAPS. If you can’t find the WAP of interest there, you can probably live without it.' [19] In 2005, using WiFi databases for geolocation was being discussed, and WiGLE, with approximately 2.4 million located access points in the database, was often mentioned.[20][21][22]

Licensing[edit]

Although the apps used to collect information are open sourced,[23] the database itself is accessed and distributed under a freeware proprietary license.[24] Commercial use of parts of the data may be bought.[25]The Android app to collect Wi-Fi hotspots and their geographic correspondent information is available under a 3-clause BSD license.[26]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^WiGLE FAQ

- ^Wigle.net: The 411 on Wireless Access Points

- ^WiGLE Statistics

- ^WiGLE Statistics (archived)

- ^Beaver, Kevin (December 16, 2015). Hacking for Dummies (5th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 372, 389. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^Turner, Andrew (Dec 18, 2006). Introduction to Neography. O'Reilly Media, Inc. p. 21. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^Field, Dave; Brandt, Andrew (Oct 27, 2004). How to Do Everything with Windows XP Home Networking: Keeping Your PC Safe. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 140. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^Proceedings: The Twentieth National Conference on Artificial Intelligence and the Seventeenth Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference. American Association for Artificial Intelligence AAAI Press. 2005. p. 20. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^Hong, Jason I-An (2005). An Architecture for Privacy-sensitve Ubiquitous Computing. University of California, Berkeley. pp. 123–125. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^Gellersen, Hans W.; Schmidt, Albrecht (Jun 23, 2005). Pervasive Computing: Third International Conference. Springer. pp. 122, 139. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^Stolarz, Damien (2005). Car PC Hacks: Tips & Tools for Geeking Your Ride. O'Reilly Media, Inc. p. 293. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^McClure, Stuart; Scambray, Joel; Kurtz, George (May 10, 2005). Hacking Exposed (5th ed.). McGraw Hill Professional. pp. 664, 690. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^McPherson, Tara (2008). Digital youth, innovation, and the unexpected. MIT Press. pp. 85, 88, 95. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^Wang, Wally (2006). Steal this Computer Book 4.0: What They Won't Tell You about the Internet. No Starch Press.

- ^'Syngress Publishing Announces the Release of 'WarDriving: Drive, Detect, Defend''. helpnetsecurity.com. Help Net Security. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^Hurley, Chris (Apr 2, 2004). WarDriving: Drive, Detect, Defend: A Guide to Wireless Security (1 ed.). Syngress. p. Cover. ISBN1-931836-03-5. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^Lentz, Chris; Kotz, David (June 1, 2003). '802.11b Wireless Network Visualization and Radiowave Propagation Modeling'(PDF). Dartmouth College Computer Science Department Senior Thesis. Technical Report TR2003-451: 2, 3. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^Glenn, Fleishman. 'WiFiMaps Encompasses the World of Wardriving, April 27, 2004'. WNN WiFi Net News. Glenn Fleishman. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^Berghel, Hal; Uecker, Jacob (December 2004). 'Wireless Infidelity II: Airjacking'(PDF). Communications of the ACM. 47 (12): 15, 19. doi:10.1145/1035134.1035149. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^Roto, Virpi; Laakso, Katri (2005). 'Mobile Guides for Locating Network Hotspots'(PDF). Workshop on HCI in Mobile Guides: 2, 5.

- ^Letchner, Julia; Fox, Dieter; LaMarca, Anthony (2005). 'Large-Scale Localization from Wireless Signal Strength'(PDF). AAAI. 05: 6. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^King, Thomas; Kopf, Stephan; Effelsberg, Wolfgang (June 2005). 'A Location System based on Sensor Fusion: Research Areas and Software Architecture'(PDF). Proc. of the 2. GI/ITG KuVS Fachgespräch Ortsbezogene Anwendungen und Dienste: 3, 5. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^https://wigle.net/tools

- ^https://wigle.net/eula.html

- ^https://wigle.net/gps/gps/main/faq/

- ^https://github.com/wiglenet/wigle-wifi-wardriving/blob/master/LICENSE

External links[edit]

- WiGLE Wifi Wardriving Android package at the F-Droid repository

- Wigle Wifi Wardriving on Google Play

Wireless networks have certainly brought a lot of convenience to our lives, allowing us to work and surf from almost anywhere—home, cafes, airports and hotels around the globe. But unfortunately, wireless connectivity has also brought convenience to hackers because it gives them the opportunity to capture all data we type into our connected computers and devices through the air, and even take control of them.

While it may sound odd to worry about bad guys snatching our personal information from what seems to be thin air, it’s more common than we’d like to believe. In fact, there are hackers who drive around searching for unsecured wireless connections (networks) using a wireless laptop and portable global positioning system (GPS) with the sole purpose of stealing your information or using your network to perform bad deeds.

We call the act of cruising for unsecured wireless networks “war driving,” and it can cause some serious trouble for you if you haven’t taken steps to safeguard your home or small office networks.

Hackers that use this technique to access data from your computer—banking and personal information—that could lead to identity theft, financial loss, or even a criminal record (if they use your network for nefarious purposes). Any computer or mobile device that is connected to your unprotected network could be accessible to the hacker.

While these are scary scenarios, the good news is that there are ways to prevent “war drivers” from gaining access to your wireless network. Be sure to check your wireless router owner’s manual for instructions on how to properly enable and configure these tips.

Driving Gps Apps

- Turn off your wireless network when you’re not home: This will minimize the chance of a hacker accessing your network.

- Change the administrator’s password on your router: Router manufacturers usually assign a default user name and password allowing you to setup and configure the router. However, hackers often know these default logins, so it’s important to change the password to something more difficult to crack.

- Enable encryption: You can set your router to allow access only to those users who enter the correct password. These passwords are encrypted (scrambled) when they are transmitted so that hackers who try to intercept your connection can’t read the information.

- Use a firewall: Firewalls can greatly reduce the chance of outsiders penetrating your network since they monitor attempts to access your system and block communications from unapproved sources. So, make sure to use the firewall that comes with your security software to provide an extra layer of defense.

War Driving Software With Gps Machine

Although war driving is a real security threat, it doesn’t have to be a hazard to your home wireless network. With a few precautions, or “defensive driving” measures, you can keep your network and your data locked down.